Preached on the Feast of St. Mary, the Virgin (transferred), April 20, 2023, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Isaiah 61:10-11

Psalm 34:1-9

Galatians 4:4-7

Luke 1:46-55

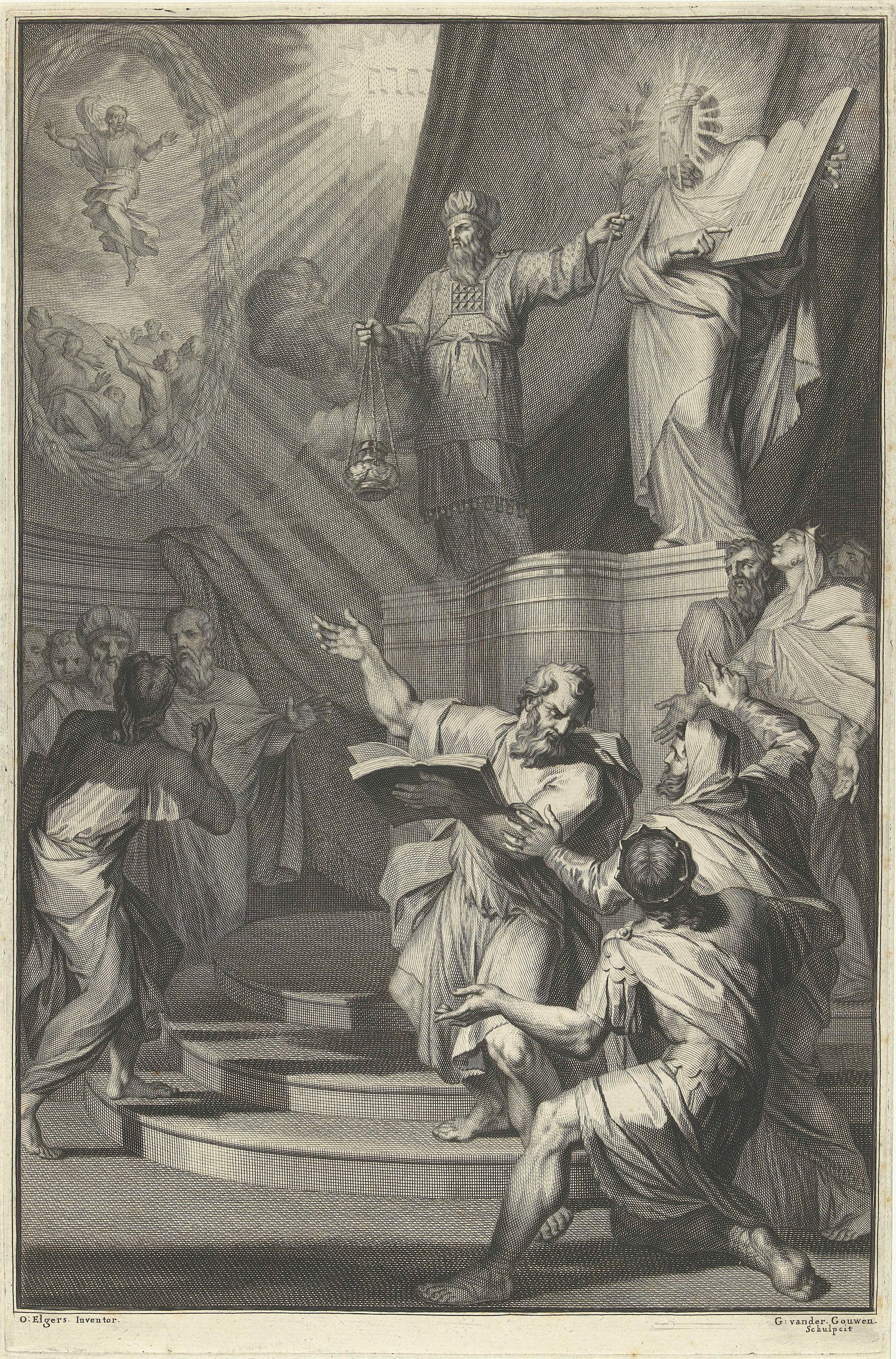

The Seven Sorrows of Mary, Mission Dolores Basilica, San Francisco, California.

It’s okay if you aren’t feeling it.

It’s okay if you aren’t over it.

It’s okay if there’s no blood going to it, no power, no light, no delight.

It’s okay. Mary can carry all of your sadness, all of your frustration, all of your anguish. Mary can carry all of your grief into the heart of God.

Mary: the name has a few meanings, but one meaning of Mary is “bitterness,” referring to the hard life of the Israelite slave Miriam (Miriam is the Hebrew origin of Mary). And the “bitterness” in Mary’s name perhaps also refers to the burial spice myrrh, a word with which Mary shares a syllable. Miriam was the sister of Moses, and though we hear her triumphant song of liberation at the shore of the Red Sea, she had been a slave—and she remained a woman in a man’s world—so she knew all too well the bitter experiences of life.

Andrea, a member of St. Paul’s, introduced me to a First Nations translation of the New Testament, a translation that reads Holy Scripture through the cultural lenses of many North American Indigenous peoples. In that fascinating version of the Christian scriptures, proper names like Luke, Paul, and Mary are changed to their meanings. Luke is not called Luke; he is called Shining Light. Paul is not Paul; he is Small Man. Mary the Lord’s mother, in turn, is called by the name Bitter Tears, while Mary Magdalene, honoring both the complexity of the name Mary and the distinctive calling of the First Apostle—she is called Strong Tears.

But back to Mary as Bitter Tears: This works, for me, as a name for the Mother of God. In a Catholic tradition that has grown up around her, the faithful pray to Mary our Lady of Sorrows, we pray to Bitter Tears, whose heart was pierced not one but seven times. Bitter Tears was pierced with grief when—

She and Joseph fled with their newborn child into Egypt;

When old Simeon, in the temple, told her the cost of her choice to give birth to Jesus—that her own soul will be pierced;

When she and Joseph lost Jesus in that same temple, when he was a precocious tween;

When she encountered her son on his path to the cross;

When she watched as he died on that cross;

When she watched as his body was taken down from the cross;

And finally when his body was laid in the tomb.

And so Bitter Tears is here for you if you aren’t feeling it, if you aren’t over it, if there’s no blood going to it, no light, no delight. We need not, in fact we should not, practice a falsely cheerful emotional perfectionism in our lives of faith. The other day I read about how the island of Maui, like so many other places, is plagued by gross inequity in housing. Many native Hawaiians have been forced to leave the state altogether because they simply can’t afford to live there, while tourism business captains reap millions from that vital but complicated industry. All this was true before the devastating wildfires that killed hundreds and destroyed Lahaina. I thought to myself, “Everything is bad, everywhere. Everything is just … bad.”

Now, that’s quite gloomy, and there is good news in the world. And, most vitally, there is the Good News of the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, Good News that was announced to Mary his mother, to Bitter Tears herself, and to Strong Tears, and to Shining Light, and finally to Small Man, Paul our patron. Mary was present, the evangelist Luke records, on the Day of Pentecost when the Holy Spirit set the Jesus Movement on fire with a thrilling sense of purpose, with a joyous—if excruciating—mission that sears and sends us even now, right here, in yet another city plagued with chronic bad news. This is all to the good! So when we pray to Bitter Tears, to the One Whose Heart Holds Seven Swords, to Mary the Mother of God, to Our Lady of Sorrows, we do not give in to nihilistic despair. That is not what Mary’s bitterness is about.

It’s just that Mary knows. She understands. She gets that we sometimes don’t feel it, we sometimes aren’t over it, we sometimes don’t feel blood going to it, we sometimes don’t see the light, we sometimes don’t feel delight. It’s okay. She gets it. And she leads us in the work of doing something with grief, of taking our grief and fashioning it into a lament—a prayer that carries our grief into God’s heart, where it is transformed into energy that heals the world.

Mary today is still a woman of sorrows, because she never got over the death of her son, even now, when both are resplendent in glory. How could she? He came back resurrected, not resuscitated, which means he was radically different, forever a stranger as well as a son, a foreigner as well as a friend. He was not resurrected to return to the same life he led before his death. And that previous life wasn’t all that delightful for Mary, either: the Gospels tell us that she was frustrated with him, sometimes even disappointed by him. And no parent who watches their child die can (or should) get over it, no matter what happens next.

But this is profound good news for us, Mary’s bitterness, Mary’s grief. It means we too can bring our grief here, and not do anything to squelch it once it’s here. We don’t have to fix it, let alone deny it. We don’t have to cover it over, or pretend it’s not important. Mary can carry all of your sadness, your frustration, your anguish. She can carry all of your grief into the heart of God.

In the Mission Dolores Basilica in San Francisco—Dolores, a name that means Sorrowful One—Mary, her heart pierced with seven swords, looks down from the ceiling. You can see a photograph of this on our bulletin cover. They placed her up, high up, in the center of a burst of cosmic light. We often imagine Mary as the woman in the Revelation to John who stands on the moon, wearing a crown of stars. Or we recognize her as Our Lady of Guadalupe, again standing on the moon, but this time wearing a star-studded gown. The cosmic Mary, the Queen of Saints: she underlines for us the human instinct to see motherhood, birth, parents and children, infusing the whole universe.

After all, we say that stars are “born,” and further that they are born in “nurseries”; and these days astronomers are excitedly telling us that the JWST telescope is taking “baby pictures” of the universe—images of the universe in its first few hundred million years, which we playfully call the universe’s “childhood.” It is odd to imagine a cosmos as a “child,” and odd to imagine a nebula “giving birth” to a star, yet we do this. Yes, this is partly because of our self-centered imagination as earth-bound mammals, but there is wisdom to be grasped here. We are onto something. We are conscious of God’s generative, loving power that, well, gave birth to the universe, and continues to do so. We are insightful when we see that creativity is maternal, paternal, parental. God is our Mother, yet so is the earth herself. And Mary—she, too, participates in the parental creativity of God.

And, like all mothers, like all parents of all genders, Mary quite naturally suffers deep sorrow. This is not maudlin or melodramatic; it is part of her parental wisdom. To give birth, or to create something, anything (I am not a parent, but I am a godparent, and I do create things): the work of creation is painful. Mary’s parenthood begins with a desperate flight—the flight of a refugee—to a foreign land; she then hears a dreadful prediction of her own suffering; a few years later she briefly loses her son in the temple, foreshadowing her ultimate loss of him in his cruciform mission; and finally she witnesses his death and burial. In all of this she is a parent, not a potentate: to create is to accept a terrible form of powerlessness. We cannot control or fully protect those to whom we give birth. Whomever—or whatever—we create is released into the universe, free, unpredictable, vulnerable.

And yet, today we hear Bitter Tears, like Miriam before her, singing a song of triumph. And note this well: she sings of triumph that has already happened: God has already lifted up the poor and scattered the proud; God has already filled the hungry and shown strength with God’s arm. It is Mary’s capacity for grief, it is the size and strength of her good heart, that empowers her to carry this profound wisdom about the universe, wisdom that sees beyond linear time, wisdom that sees how all things are culminating in God’s triumphant light. Bitter Tears is not glib; she is nobody’s fool; she does not promise the moon, even as we imagine her standing on it. Grief in the heart of Our Lady of Sorrows becomes a source of fierce wisdom and fearsome strength. She is fortified by her mature, intelligent, courageous response to the swords that pierce her painfully. Bitter Tears is brave.

And she, in turn, pierces our hearts, pierces them until they break, and break open, in compassion for all who suffer, for all who grieve, for all who weep. Bitter Tears is a prophet of God, among her other identities and titles, and she says to us what old Simeon said to her. She says it with faith, with love, and with a ferocious determination. She says it to send us from here, our hearts breaking but strong; our minds pondering but open; our bodies broken but strengthened. She says to all of us, to each of us, these terrible yet oddly joyful words, words that ring through the whole cosmos:

A sword will pierce your own soul, too.