Preached on the Feast of the Transfiguration of our Lord, August 6, 2023, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Exodus 34:29-35

Psalm 99

2 Peter 1:13-21

Luke 9:28-36

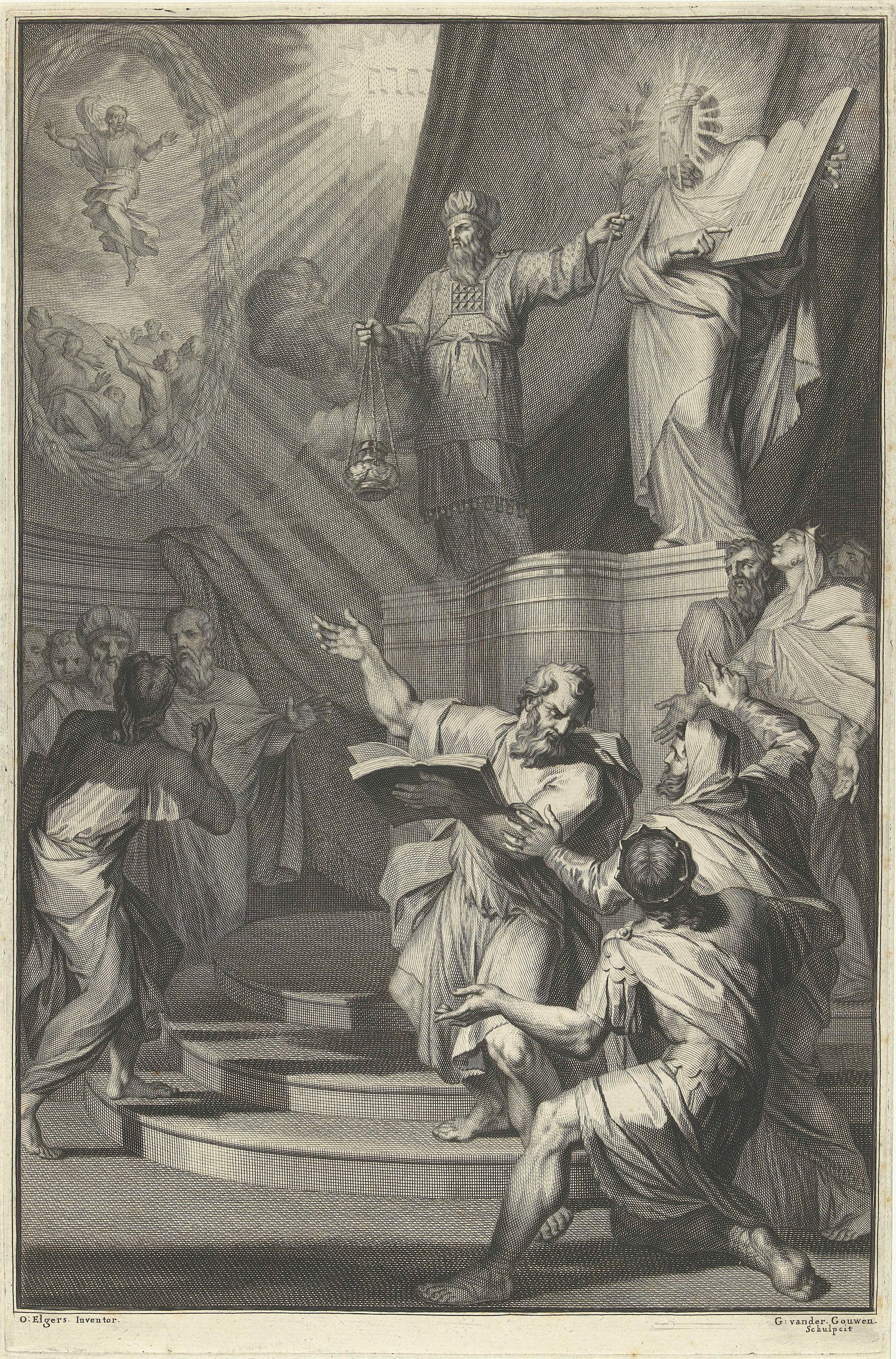

Moses and Aaron Reveal the Ten Words, by Gilliam van der Gouwen.

One day, when I was a young kid in southwest Minnesota, I was down in the basement of our house, and I was playing with fire. I held a piece of paper against the exposed coils of an old-style space heater, the kind where the red coils were easily accessed through a thin wire casing. The edge of the paper glowed with a new fire, and the fire licked around the paper until I successfully blew it out. The whole experience was vivid with sensory details: brightness, heat, curling ash, the acrid yet pleasant fragrance of the flame.

Then I heard a rustling and turned to my right. There stood my mother, watching me silently. I felt a flood of fear.

She quietly but firmly told me to go upstairs, and I remember sitting in the living room while my parents calmly asked me what I had done, and why. They were reasonable, sensible, appropriate. In fact it’s possible my father wasn’t even there: memory is tricky; if he was there, he was like Aaron, the brother of Moses – immensely important, but quiet. My parents gave me some basic reminders about the dangers of playing with fire.

All was well, but I felt shaken, because in that terrible moment when she confronted me, my mother’s face was not that of a friend, or at least an easy, consoling friend. Her face seemed to shine with fire.

Fire burns everywhere in this story: the literal fire of the space heater of course; my mother’s fiery expression; and, most vitally, the fire that burns in the human conscience – the searing sense that one has done the wrong thing. The only way my mother can be fearsome in that situation is if we both believe that there are good behaviors and there are bad behaviors, and I did one of the bad ones. If I had been a different kid, one who was less in touch with the rules, one who was more foolhardy, brazen, oppositional – then my mother wouldn’t have frightened me so much in that moment. “Whoops,” that other kid might say, “I’m busted.” That defiant kind of kid could have even tried to bluster his way out of it. “Come on!” he might say breezily to his mother. “It’s no big deal. Chill, mom.”

But my mother had great power. She was just the type of person who would return to the camp after a mountaintop encounter with God, her face shining with God’s searing justice, God’s terrible righteousness, God’s bone-rattling, awful awareness of everything those foolish people did. My mother – who never permitted us to call her “Mom” – she was, well, Mosaic. She was, like Moses, a leader of her people, a friend of God, and so, in her own way, she bore on her face God’s own terrible power. Perhaps you know someone like this in your own life. Perhaps that person is you yourself. It is not always easy to know such a person, yet I hope you do.

There is one surprising reason why, throughout Holy Scripture, the most common greeting we hear from the Angels – from God’s messengers – is the command, “Do not be afraid.” They tell us not to be afraid, again and again, not because of all the dreadful things in this world: suffering, illness, violence, oppression, failure, despair, death. No, God’s messengers repeatedly say “Do not be afraid” because God is terrifying.

Now, we speak of God as Love, and we are right to do so: Augustine teaches that the Holy Trinity is the Lover, the Beloved, and Love itself. And the Church these days is preoccupied with hospitality, again with good reason: all too often, the church swings its door shut in the faces of queer people, persons of color, differently abled people, neuro-diverse folks, those who suffer addiction, those who commit crimes, unhoused people, low-income people, children, youth, sole parents, elders, and others. We are right to imagine Jesus as our open-minded, open-hearted friend, our shepherd and exemplar, the One whose burden is light, because his burden is always shared. We are right to recognize Jesus as the Gentle One who saves us from the terrible sin of distorting the Body of Christ into an elite club of insiders.

But – though God is Love, the God of Love is terrifying. Holy Scripture faithfully records this truth. The psalmist sings that God rides upon the clouds of the storm; that the voice of God makes the oak trees writhe, and strips the forest bare. God is terrifying because Almighty God knows us, and Almighty God is close to us.

I learned as a couples therapist that there are two ways to distance yourself from someone you love who upsets you: you can reduce how important they are to you, or you can reduce how close they are to you. But God denies us the ability to do either of these things. God knows us intimately, having created us by breathing God’s own Spirit into us. So I can present a public face, but God will always know the real me, and therefore God will always remain ultimately important to me. (“Where can I flee from your presence?!” the psalmist cries.) Like my mother standing in that basement doorway, God sees, God knows: God is often described as fire, or fiery; and it is God’s fire that burns in the cauldron of the human conscience.

And God, in turn, is forever close to us: in our most joyful moments of liberation and celebration, yes, but also in our most vexing crises, in our deepest grief, and in the hour of our death. God’s Spirit moves vitally in the anxious heart of a parent, and God’s Spirit moves playfully in the curious, questioning heart of their child; God’s Spirit blows powerfully through the crucible moments of youth and midlife; God’s Spirit breaks the lock of the offender’s jail cell; God’s Spirit confronts the wrongdoer with the truth; God’s Spirit animates the doctor as she gives her patient a grim prognosis; God’s Spirit moves warmly along our arthritic bones; and God finally meets us at our end. God is transcendent, yet immanent; God is ultimately important to us, and devastatingly close to us. Everything and everyone else is trivial.

And so, perhaps we can empathize with the friends of Jesus who were knocked off their feet with terror at the sight of him blazing in glory on the mountain. Jesus, the New Moses, was not just their soft friend, not just the warm rabbi who practiced radical welcome in his ministry to the outcasts. He stood before them in might, and he was glowing.

Or was he glowering? There is always a terrible ferocity in God’s glory. We rehearse this truth in our best stories, the ones with the kindly old wizard with twinkling eyes who transforms at the time of crisis into a mighty, fearsome wonder worker. Saint Nicholas wasn’t just a genial grandpa who gave treats to kids: he is remembered for his harsh rebukes, his bracing exhortations. Jesus is not just my reassuring friend: he is also the Stranger, the deeply unsettling Risen One, not a ghost, but also not simply a relatable human companion. “Simon, son of John,” Jesus intones in a post-Resurrection breakfast, and immediately Peter knows he’s in trouble: his three denials of his Lord are now going to be repaired, painfully, by this terrifying Stranger.

We pray to this Stranger, to God who is Fire, to God who shines with terrifying justice – we pray in many ways. One way is through visual images. We write icons to guide our prayer, and engrave images to grasp (at least in our imagination) the fierce glory of God. On today’s bulletin cover you will see that our copy machine cannot do justice to an engraving of Moses as he shines with God’s light. You’ll find a better copy of this engraving in the narthex, and those of you on livestream can see it now. I am struck in this image by the curious expression on the shining face of Moses: he seems almost glum. Or he’s just grim, gritty, grave. His human face seems blunted by the light of God. His physical body recedes behind the light.

And here, just below me, you will find an icon of the Transfiguration, written by Kristina Prokhorova in 2003 for our own Steven Iverson and Ralph Carskadden. I encourage you to take a closer look when you come up for Communion, or after mass. I am drawn to the terrified eyes of the disciples in this image. One of them has covered his face in his hands, making room for only one eye to peek out.

All this terror, all this fearful squinting and trembling in God’s presence – this is not about the humiliation of the human person. It is paradoxically about our restoration in dignity and gladness as God’s people. We fear God not because God is unjust, let alone unjustly violent: we fear God because God who is Fire burns away the worst in us to reveal the best in us, and that is scary. We fear God because God who is Love is found beside us in our most desperate hours of need, and that is sobering. We fear God because God who is our Friend is the one friend we need the most, the Friend who knows us best and remains unnervingly close, and that is good news – but it is harrowing.

Do not be afraid. God is terrifying, but God is just, God is good, and God is with us as we descend from the Mountain of Transfiguration, together, shining with God’s light, burning with God’s wisdom, warmed with God’s searing love.

And as we descend the mountain together, I have to say: you may not realize this, but you are shining with God’s own light – as we all do. And so you, too, are a little scary.