Preached on the First Sunday in Lent (Year A), February 22, 2026, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Genesis 2:15-17; 3:1-7

Psalm 32

Romans 5:12-19

Matthew 4:1-11

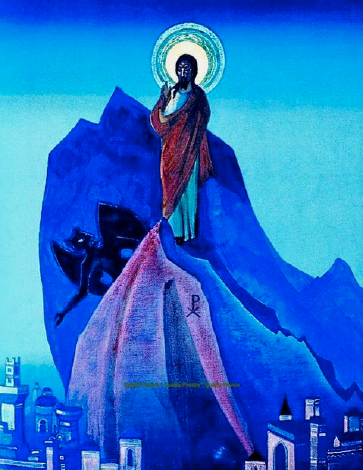

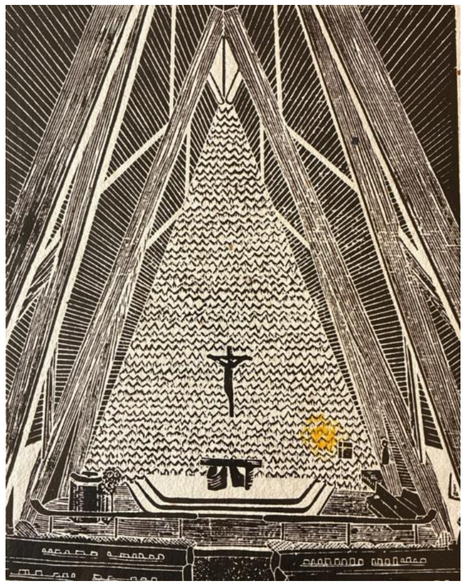

Temptation of Christ, by Nicholas Roerich

A reading from a (slightly redacted) song by Britney Spears.

You wanna?

You wanna?

You wanna hot body? You wanna Bugatti?

You wanna Maserati?

You better work.

You wanna Lamborghini? Sip martinis?

Look hot in a bikini?

You better work.

You wanna live fancy, live in a big mansion,

party in France?

You better work.

You better work.

Here ends the reading.

Britney did not coin the phrase, “You better work.” RuPaul made it famous, and it is a time-honored expression in queer culture. One day, when the gay comedian Matteo Lane was in a restaurant in Rome and discovered that Oprah Winfrey was also there, he thought carefully about what to say to her, something that would quickly telegraph “I’m gay, I’m American, and she looks great.” He cheerfully snapped, “You better work!”. Oprah, being Oprah, didn’t miss a beat. “You better work!” she shot back, with a smile.

And so, for us, inspired by Britney, Matteo, and Oprah, the holy season of Lent begins. Lent is here: we better work.

On this first Sunday in Lent, we are taken into the primordial garden of creation where God asks the human one, “Where are you?” Later, when God sends the humans out from the garden, God says to them, and I’m paraphrasing, “You better work.”

We then find ourselves today in the wilderness of the Negev desert, where the new Human One needs no reminding from Britney or Matteo or Oprah: he is already hard at work, on a six-week spiritual project. In his wilderness sojourn, he is tested by the Accuser. He passes the tests, and then he’s waited on by God’s angelic and hard-working diaconal messengers. Like our friends on Wednesday evenings in Lent, they fill him up with soup and bread.

In these classic biblical scenes, alongside the mighty and sometimes troubling company of Adam, Eve, the Accuser, the angels, and Christ himself, we might discern a lot of things; we might think and feel a lot of things; and we might try in various ways to make sense of these momentous conversations, these intense encounters, these ultimate experiences of human ones in crisis, in both gardens and wastelands.

We can situate ourselves anywhere we like in these scenes that we proclaim at the beginning of Lent. Are you Adam, on the run but aware of your absurd culpability, and all too aware that you can’t outrun God, since God finds you no matter where you go, because God is found even inside your own most private thoughts and feelings? Maybe you’re Eve, problematized and blamed for your dubious choices, even though you’re actually just an intelligent, courageous woman struggling toward a new enlightenment. Or maybe you identify with Jesus, finding yourself these days in a desert of difficulty, in a wilderness of worry, in a landscape of lament. If you’re anything like Jesus, then you will be tested in these hard times.

Or maybe you’re the one doing the testing, the Accuser, in Hebrew the satan. Maybe you’re a devil’s advocate, if not the devil himself. Maybe your journey of faith raises up in you the spirit of the skeptic, the calling of the critic. And even though this satanic figure in biblical stories is typically portrayed flatly as evil, maybe it’s not that simple. Maybe, if you identify with the Accuser — maybe you are, in your own way, not just a gadfly, but also a prophet, albeit a troubled and dreadful one. Maybe you’re a prophet because you provoke and challenge others — you goad and poke at us, disturbing our comfortable arrangements, questioning our unconscious assumptions. As our bracing ‘accuser,’ you test and strengthen us. You might not be comfortable or widely liked, but this could be a useful role for you in this community.

But it would be much more comfortable and pleasant for you around here if you found yourself in the story at the very end, when the angels come to wait on Jesus. Maybe you’re a waiter, a server, a helper, a deacon. Maybe you’re just cooking soup and helping out. If so, that would be a life-giving, holy calling.

But in all of this, no matter who we are, no matter how we feel or what we think as we tell ourselves once again these ancient stories of salvation, in all of this, I believe we hear this instruction from God, as Lent begins, this invitation, this calling:

Girl, you better work.

Now, let me hasten to assure you that I’m not preaching works righteousness. We can’t justify or redeem ourselves by being extremely well behaved or by logging ten thousand volunteer hours. That heresy, let me be clear, is beneath us. It was rejected as long ago as St. Paul’s time. Lent is not a fitness challenge at the gym, with a star chart at the reception desk, something I confess is actually part of my life right now, at a gym in Ballard. I can stick as many stars as I want on that colorful chart: God won’t love me any more. And I might actually be more lovable if I weren’t in achievement mode so much.

No, the “You better work” of Lent is better explained by Saint Paul in his letter to the Romans. Paul tells us that “if, because of [Adam’s] trespass, death exercised dominion through [Adam], much more surely will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness exercise dominion in life through the one man, Jesus Christ.”

Let me break that down a little bit. As the children of Adam, we fall short, and death dominates our world; death dominates us. Adam and Eve eat fruit in the garden — they receive the good gifts of God — but they do this in a self-directed way that diminishes health, drives them away from each other, and damages creation. We inherit that tradition as fallible, vulnerable human beings.

But we also receive free grace and righteousness from Christ, and so we exercise dominion in life: life dominates our world; life dominates us; we rise up in life. And we rise up to work hard, together, to share the creative, regenerative gifts of God with everyone we meet and know. When God says (again, this is an absurd paraphrase!) “You better work,” the work is outward-focused and life-giving: we receive good gifts from God, we share those gifts here, and we distribute those gifts beyond here, working to restore God’s living garden.

(Quick sidebar on the churchy phrase, “gift of righteousness”: the biblical word righteousness refers to a right relationship, a sound emotional attachment, a strong intellectual engagement, a life-giving relational bond. God’s gift of righteousness through Christ pulls us from a path of death onto a new path of life. Righteousness is simply us being and doing what God intends for us.)

But all of this might be said best in the table prayer we will say a bit later in this liturgy. When we gather once again around this table, our hearts will overflow with thanksgiving. That’s what Eucharist means: thanksgiving. But then, when we say today’s particular Eucharistic Prayer, we will ask God for this: “Deliver us from the presumption of coming to this Table for solace only and not for strength; for pardon only and not for renewal.” As much as this is a welcome Table, and as much as the gifts laid on this Table are food for the starving, this Table is also an energy station for runners in a great race. This Table is fuel for our life-giving labors of love. This Table gives us strength and renewal so that we can go to work.

No fancy Italian car awaits us as the fruit of our labors, in Lent or beyond. The dominion of life calls us far higher than that, and rewards us far better. This will be the fruit, the joy, the glory of our Lenten labors, as sung not by Britney but by the ancient psalmist:

“All the faithful will make their prayers to you in time of trouble; when the great waters overflow, they shall not reach them. You are my hiding-place; you preserve me from trouble; you surround me with shouts of deliverance. Mercy embraces those who trust in the Lord. Be glad, you righteous, and rejoice in the Lord; shout for joy, all who are true of heart!”