Preached on the Fifteenth Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 17B), September 1, 2024, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Phillip Lienau.

Song of Solomon 2:8-13

Psalm 45:1-2, 7-10

James 1:17-27

Mark 7:1-8, 14-15, 21-23

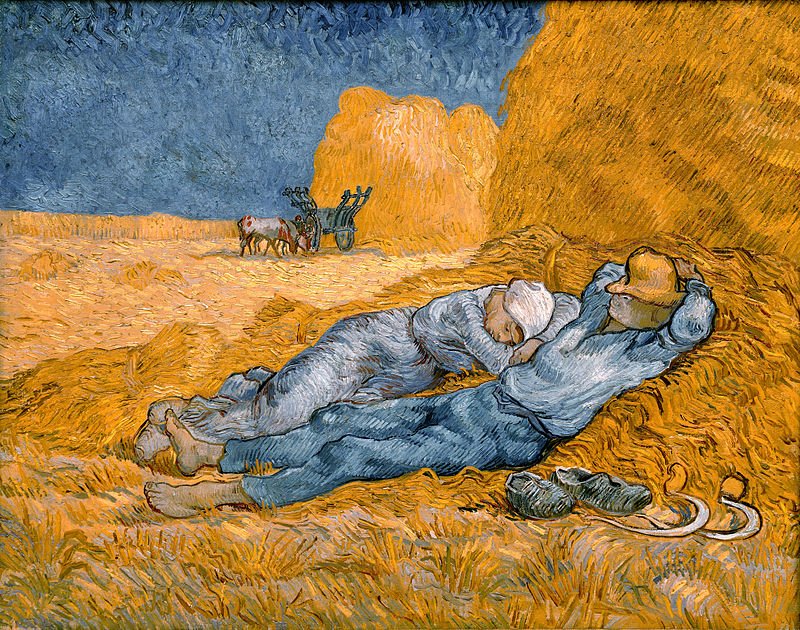

'Arise my love ... and come away...', by Cláudio Pastro

The voice of my beloved! Look, he comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills.

My beloved speaks, and says to me: “Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.”

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

These verses are from our first reading, from the Song of Solomon. There is a long tradition in both Judaism and Christianity of reading this book of love poetry as an allegory for the mystical relationship of our loving God with us, God’s beloved people, individually as well as collectively.

I invite you this morning to join me in letting that sink in for a moment. What if we wrote love poetry to God? What if God wrote love poetry to us? Let’s enjoy those verses again, with this in mind.

The voice of my beloved God! Look, God comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills. My beloved God speaks and says to me, and you, to each and every one of us: “Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.”

The verses continue with images of springtime and bounty: flowers and blossoms, fruit, and fragrance. The time of singing has come.

We are reminded of this agrarian imagery in our collect of the day: Graft, as a gardener might – graft in our hearts the love, the love of your name. Increase, as in a bounteous harvest, increase in us true religion. Nourish, as with warm sun and cool rain, nourish us with all goodness; and bring forth in us the fruit, the fruit of good works.

Can you feel the warm sun and the cool rain, the nourishment of God’s love, and the fruit of that love in your heart?

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

But come away from what? In these verses the lover visits the beloved who is behind a wall. The question then, is what is our wall? What wall is keeping us from following God, from answering God’s call to us?

I expect each of us might have our own answers to that question, our own wall we have built between us and God, or perhaps a wall someone else built, and we inherited, or adopted, and haven’t had the courage yet to topple.

Jesus in today’s Gospel lists several intentions of the human heart that can build or maintain that wall between us and God, and between us and each other: fornication, theft, murder, adultery, avarice, wickedness, deceit, licentiousness, envy, slander, pride, folly.

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away from these intentions.

Well, that is sometimes easier said than done. Although, I find it rare that people willingly choose evil before the good, at least to start. Usually something happens that drives people to desperation.

Take the beginning of the Gospel passage, for instance.

Right away it is important to recognize that it’s problematic in terms of a legacy of anti-Jewish sentiment in Christianity. Modern biblical scholarship teaches us that the writer of the Gospel of Mark seems to lack comprehensive knowledge of the full variety of 1st-century Jewish beliefs and practices about food and washing. So when we hear in the Gospel generalizations such as the phrase, “all the Jews,” we are probably not hearing the whole truth. This is important because generalizations like this are too easily used to justify oppression.

So let’s be clear. As best as historians can tell, there was in Jesus’ time considerable variety in Jewish ritual practice, and interpretation of, and adherence to, Mosaic law. It is not appropriate to interpret Jesus in this Gospel throwing out Jewish law, or disrespecting the work of his fellow Jews to live into the covenant with God. If anything, Jesus seems pretty consistent in his critique of hypocrisy of any kind, not just that of certain Jewish religious authorities, and of putting human-devised traditions above God’s commandments which can be summarized in the love of God and love of neighbor.

Instead of getting caught up in the details of who is allowed to eat what and when, I encourage us to hear in this text an echo of trauma and fear coming out of an early Christian community grappling with its identity as something other than Jewish. That phrase is important: something other. Early Christians like the community out of which arose the Gospel of Mark, sometimes felt like the other. And sometimes our Christian spiritual ancestors did what many people do when they feel traumatized: they took their hurt and their fear of being treated as other, and passed that trauma on to someone else, in this case, as is too often the case in Christian history, onto Jews, treated here as a monolithic other.

I do not believe that Jesus was in the business of othering people, of building walls between an us and a them, between an us and an other.

Arise, my love, my fair one and come away.

Yet rather than toss out some of the language and ideas of this passage of the Gospel of Mark, let’s recognize the human limitations of our ancestors, and recognize our own limitations, and learn from this, with gentleness and compassion.

Let us admit the times we are hurt and afraid, and might react by pushing each other away. Let’s admit the times we might seek to belong in an us that is defined by not being them, the other.

I hear Jesus recognizing an attempt by some of his fellow Jews to build walls between themselves and his followers, and I hear Jesus inviting them, and us, to look beyond these walls we build out of hurt and fear, and see each other as God sees us, as beloved, every one.

Arise, my love, my fair one, and come away.

Let us come away from our walls. We don’t need them.

For God so loved the Cosmos that God came down from heaven: God was incarnate from the Holy Spirit and the Blessed Virgin Mary, and became truly human. Look, he comes, leaping upon the mountains, bounding over the hills. See, the love of God for us is so great, God overcomes every barrier, crosses every distance, in God’s reaching out to us in love.

Arise my love, my fair one, and come away from your fear, for now the winter of death is past, the rain of sorrow is over and gone. Jesus, who for our sake was crucified, suffered death and was buried, on the third day rose again, and flowers appear on the earth, and oh, the time of singing has come.

The time of the singing of angels has come, the time of singing of every stone, every grain of sand and every star in the heavens, and every plant and animal, and every one of us has come. Holy, holy, holy Lord, God of power and might, Heaven and earth are full of your glory!

Let us accept God’s invitation to all of us to come to God’s bounteous table to be nourished with all goodness of God’s love for us, so that we may go forth with the holy Name of God grafted in our hearts, that God may bring forth in us the fruit of good works.

Oh, my fellow beloved, let us with joy hear together our loving God calling to us:

Arise, my love, my fair one, come away.