Remarks for Shared Homily at 5:00pm Vespers with Holy Eucharist

Mark 2:23-3:6

St. Paul’s Episcopal Church

Second Sunday after Pentecost (Proper 4B)

Mark Lloyd Taylor, Ph.D.

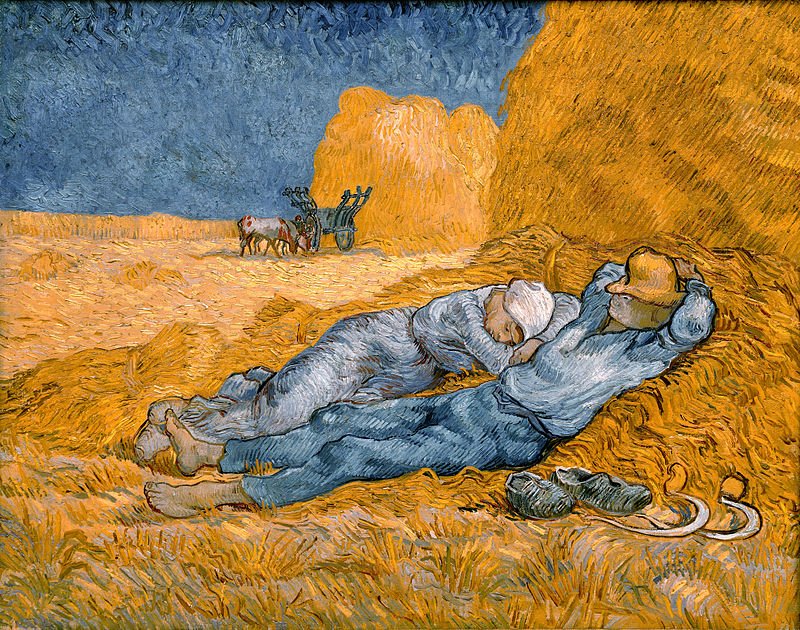

Noon, rest from work, by Vincent Van Gogh

Well, that was the first time in two months we’ve heard a reading from the gospel of Mark – even though this is Year B in our Sunday lectionary cycle, the year that leans into Mark. Most of our gospel readings during the Easter season and on through Pentecost and Trinity Sundays came from John, with a few from Luke. But this evening we return to Mark’s gospel and now Sunday after Sunday for the next six months – with one little detour through John in August – we’ll have the opportunity to live into Mark’s distinctive and distinctively different way of telling the story of Jesus. To get ready for that immersion experience, we’re all invited to gather upstairs on Sunday, June 16 at 2:00pm when a little troupe of actor-storytellers will perform the gospel of Mark – all of it, from jarringly abrupt beginning to mysteriously open-ended ending.

This evening, however, we don’t need to wrestle with the whole gospel of Mark, just those two little stories we heard Linzi [The Rev. Linzi Stahlecker] read from the end of chapter 2 and the beginning of chapter 3. Both take place on sabbath days. Both involve what the sabbath does and doesn’t, should and shouldn’t, mean. The stakes couldn’t be higher. For after hearing Jesus’ sabbath words and observing his sabbath actions, here’s the verdict rendered by the religious and political authorities: “The Pharisees went out and immediately conspired with the Herodians against Jesus, how to destroy him.” Not how to chastise him or pull him back or restrain him, but how to destroy him.

+++

And so, Jesus and his opponents and the sabbath and us. We need to be careful. I need to be careful. What we call Sunday, the Lord’s Day, the eighth day, is not the sabbath of our Jewish siblings. But they’re related, intertwined even – not always for the good of Christians or Jews. We need, I need, to avoid the self-righteous Christian stereotype that the six hundred thirteen commandments in the law of Moses are oppressive and life-denying. I once had a conservative Jewish rabbi as a colleague – and it’s true that he couldn’t come to my home and eat dinner because we didn’t keep a kosher kitchen, but he invited us to several sabbath dinners in his home with his family and they were occasions full of life and joy and blessing. Another time, Larry and I were driving back from a faculty retreat when a rainbow appeared on the opposite side of the Hudson River. He immediately started chanting a prayer of thanksgiving in Hebrew – remember the Noah story! Larry was surprised that we Christians don’t have a similar prayer in our tradition. I need to be careful, we need to be careful, as we think about sabbath not to bear false witness against our Jewish siblings.

We find one way of framing the meaning of sabbath in the book of Genesis (2:1-3): “Thus the heavens and the earth were finished, and all their multitude. And on the seventh day God finished the work God had done, and God rested on the seventh day….So God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work God had done in creation.” This narrative gets carried over into the book of Exodus as the fourth of the Ten Commandments (20:8-11). Sabbath rest. And that’s what angers the Pharisees in our two stories from Mark’s gospel: Why do your disciples do what is not lawful on the sabbath by plucking heads of grain in the fields? Why do you engage in the work of healing a man on the sabbath?

As a kid growing up, we used the words sabbath and Sunday interchangeably. I grew up in the Church of the Nazarene, part of the so-called American holiness movement. We were a little different. We didn’t smoke. We didn’t drink. We didn’t play cards – well, we could play Rook!, but not those evil poker cards with their clubs and spades, jacks and queens. We didn’t go to movies. And we didn’t watch television on Sunday – and so I missed the Beatles’ appearance on the Ed Sullivan show. But I grew up Nazarene in eastern Massachusetts, which, by the 1960s, was predominately Roman Catholic, although its cultural and religious roots go back to the Puritans of the 1600s. When I was a kid, Massachusetts still had what were called “blue laws” that kept most shops and other businesses closed on Sundays. Those laws have since been repealed. Capitalism won out. But – and here’s my point – for me, growing up, Sunday was not so much about rest as abstinence. Sabbath abstinence. See no evil. Hear no evil. Avoid the evil attractions and entertainments of the world.

Now there’s nothing wrong with abstinence. There are very good reasons why some people abstain from eating pork or drinking alcoholic beverages or burning fossil fuels. And there’s nothing wrong with rest. The problem – whether we are Christians or Jews or some other faith or no faith at all – is when some people enjoy the privilege, the leisure, to rest, while others must work hard all weekend just to make a living. The problem is when my abstinence – or whatever my ethical or religious symbols and stories, rituals and practices happen to be – when my abstinence causes me to believe I’m better than other people; causes me to forget that they, too, are God’s Beloved.

But there’s a second edition of the Ten Commandments in the book of Deuteronomy; the law of Moses 2.0. Here the sabbath is traced back to the liberation of the people of Israel from Egyptian slavery, rather than God’s rest from the work of creation. And the insistence here is that sabbath rest is for all, not just some. “Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy as the LORD your God commanded you. Six days you shall labor and do your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the LORD your God; you shall not do any work – you, or your son or your daughter, or your male or female slave, or your ox or your donkey, or any of your livestock, or the resident alien in your towns, so that your male and female slave may rest as well as you. Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the LORD your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore, the LORD your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day” (Deuteronomy 5:12-15).

Sabbath liberation. That’s what Jesus’ words and actions are about in our gospel reading from Mark. “The sabbath was made for humankind, and not humankind for the sabbath” (2:27). The sabbath is not an end in itself, but a means to address human need for the sake of human flourishing. Whether it’s hunger for bread, or hunger for inclusion, equality, and justice. For Jesus, the point of sabbath rest is restoration. “Come forward,” he says to the man with the withered hand – and then asks his opponents: “is it lawful to do good or to do harm on the sabbath, to save life or to kill?” (3:3-4) Grieved at their hardness of heart, Jesus invites, no, Jesus commands the man – “‘Stretch out your hand.’ He stretched it out, and his hand was restored” (5). Sabbath restoration.

+++

I wonder how these three different meanings of sabbath sit with you? Abstinence. Rest. Liberation and restoration. I wonder how we might perform sabbath this Sunday evening? Embody sabbath? Put it on and act it out? Imagine three stations set up around this worship space as prompts.

A chair turned around backwards for sabbath abstinence. Hands off. Eyes shut. Ears covered.

Then a different chair, a rocking chair. Sabbath rest. Sit. Sit back. Recline even.

And for sabbath liberation and restoration: a work bench with tools and gloves. Come forward. Stretch out your hand. Hands on.

Do you need to visit one of these three stations in particular, for a while, and sit there? Abstinence? Rest? Liberation and restoration? Or how might each station complement and correct the others for you?

I invite your responses.

Resource: Laurel Tallent for likening my imaginary stations to the Stations of the Cross we visit as part of our Lenten practice.