Preached on the Feast of All Saints (Year A, transferred), November 5, 2023, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Revelation 7:9-17

Psalm 34:1-10, 22

1 John 3:1-3

Matthew 5:1-12

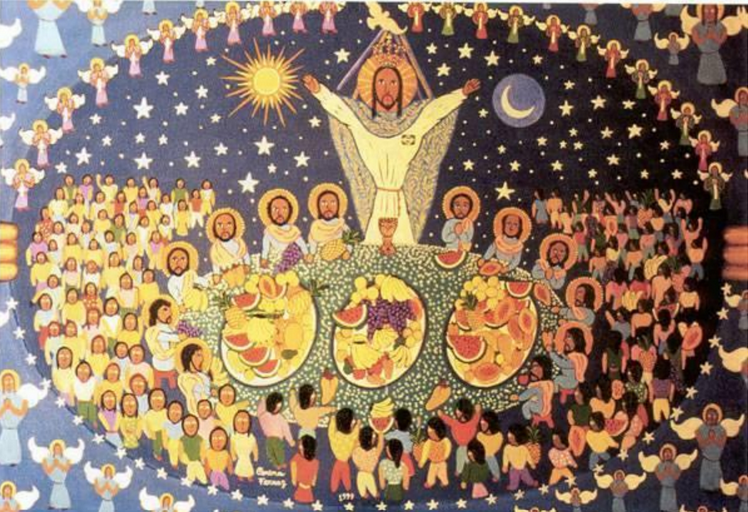

All saints, by Emilia Misiura

I was talking to myself the other day. (I like to talk to myself; I am one of my best listeners.) “Stephen, I think you need to talk to the parish a little,” I said, quietly, in my heart. “I think you need to talk to your folks about two big things that happened this week. These events affect them; they affect our life together here. Fill them in,” I finished, in my little self-talk. “Let them hear from you.” And so I will.

I begin with something difficult that happened to one of us, and I am choosing carefully, and cautiously, to call him by name. I want to respect his personal privacy, and most importantly I do not want to establish a double standard where we discuss some of us by name – usually those of us who lack a particular privilege – while being diplomatically circumspect about others. In this case, the privilege this person lacks is wealth privilege. But the events of recent days compel me to speak with responsible candor. And so will I do that, with exceeding, anxious care.

This week I initiated the relocation of Houston, a member of St. Paul’s who camped on our parking strip. Now, please hear me: Houston remains one of us, and I believe he has a future with St. Paul’s. He pledged to our capital campaign, and he met that pledge; he was a presenter at the Celebration of New Ministry this past February; for years now he has volunteered a lot of time to help us with safety and maintenance in and around our garden. But Houston’s arrangement with us became problematic, and though Houston was but one participant in that arrangement, he unfortunately bore the brunt of the consequences. Speaking only for myself, my learning curve is steep in the work of ministering alongside our neighbors. It is a complicated ministry.

I deeply respect and care for – indeed I love – Houston. I pray for him regularly. I think you should pray for him, too. Pray for Houston: he is your sibling. He now lives nearby, but not on our block. He expressed deep dissatisfaction with his church home, and I understand why. I truly understand.

“Blessed is Houston, who is one of those who mourn,” our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ proclaims today, in my hearing. “Blessed is Houston, for he will be comforted.” I believe that Houston mourns. In my experience of him – and please hear me say that I am sharing my experience; I am not speaking for him – in my experience, Houston bears up beneath a deep and debilitating sorrow. He is a powerful, resourceful survivor, but Houston is deeply grieved, striving to survive in a city that cares very little, if at all, for his welfare. I experience Houston, who like all of us shines with God’s image and likeness, as one of all too many in Seattle who cry a silent yet poignant lament of grief.

If Houston does mourn, he is far from alone. We are surrounded by grieving humans. They sit in these pews. They camp on that parking strip. They stand in this pulpit. I, too, am mourning. I believe that I am not a fraction as wounded and vulnerable as Houston, but I am lamenting this world so harshly riven by seemingly intractable conflict.

And that brings me to the second big thing that happened this week, that led me to tell myself, “I think you need to talk to the parish a little.”

I published a blog post with my thoughts about Gaza and Israel. I did so with trepidation, but I think with too little trepidation, given some sharp responses I received. This is a dreadfully polarizing topic, but I felt I had to address it, as a public faith leader, and as a friend and family member of people who are closely involved.

My position is complicated. I share in the depths of my being a passion for peace with justice for all people in what we problematically call the “Holy Land,” and I pray for the Palestinian people in particular, again and again. But I also have family and friends who are in Israel right now, and I understand some of the political choices Israel has made, both in recent weeks and across seven and a half decades. I appreciate the predicaments everyone in the region has faced since Israel’s founding, and I believe that right now Israel is faced with a small number of terrible choices. And while I harbor grave concerns about the Israeli government, I have many of the same concerns about my own government, and I am outraged by the actions and statements of Hamas.

But more personally, and more viscerally, I empathize deeply with residents of Gaza who live in such chronic and desperate peril, but I also empathize with Israelis who have seen their children slaughtered and their family members abducted by terrorists. And while I pray for a peaceful and just ceasefire, I also struggle to imagine how any nation could not respond to a terrorist attack with some form of military retaliation. And finally we arrive at the most critical dilemma in all of this: all military action, all violent political action, destroys innocent life.

All of this takes me back to the list Jesus gives us of those who are “blessed,” or in some translations, those who are “happy.” Happy are those like Houston who mourn, for they will be comforted. There are countless desperate mourners in Gaza, in the West Bank, in Israel, throughout the Middle East, across the whole war-torn world. But Jesus also says, “Happy are the peacemakers, for they will be called children of God.

I want to be a peacemaker. I want to be a peacemaker when I am working with a few of you to move our sibling in Christ from his dwelling at the edge of our property, while keeping him secure at the center of our hearts; and I want to be a peacemaker when he understandably rises up in anger when we do this. I want to be a peacemaker when I pray for family and friends in peril, and I want to be a peacemaker when I confront more anger, this time against me personally for comments I made about a dreadful war. I want to be a peacemaker who understands another peacemaker’s critique of my position.

Now, I want more than to be a peacemaker; I also want some arguments: I want to persuade others to share my views. (And not to digress too much, but I have an argument or two with Houston as well, who inspired conflicted feelings in me and others, and did not just feel them himself.) But more deeply I want true, and just, and lasting peace – peace between me and the persons upset by my Gaza/Israel post, peace between all of us at St. Paul’s, peace between those who are dismayed by the Israeli government and those who work in and for that same government, peace that rises beyond human understanding, peace that comes only from the Holy One. That is what I most want.

And so now, as we begin another week on this troubled block; another week in this grieving city; another week on a planet deeply wounded by war, atrocity, terror, and rage; as we begin another week here, we pursue peace by … baptizing. We will lead our sibling in Christ, Michael, to the font of Holy Baptism, to the roiling waters over which the Holy Spirit hovers, to the river where the Word of God is heard, and we will baptize Michael in the holy name of God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. Michael plunges into the cruciform life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ; Michael wades safely through the waves that cast the horse and rider of oppression into the sea; Michael joins us in God’s mission to liberate all of the oppressed – all of them, even those, including us, who are complicit in the oppression of others; Michael takes his place at this Table of Thanksgiving, where he is strengthened boldly to enter a new week, and then another, and then another, alongside us.

In Holy Baptism, Michael becomes a “soldier, faithful, true, and bold,” to quote today’s grand entrance hymn, For All the Saints. A soldier: now that’s a potentially troubling image. I know and have known soldiers, good ones, yet I expect some of you find their vocation disturbing. Militant imagery is especially dangerous to use in any religious context, and as more than one person has said, all wars are crimes. So why do we use the image of “soldier” when we talk about all the saints?

Because we are fighting, that’s why. We are fighting the force of death that bears down upon so many neighbors, many of them unhoused, in our immediate midst. We are fighting the force of fear that prompts us to recoil from the world’s problems rather than face them together. We are fighting the force of discord that tempts us to argue about false dichotomies rather than grapple with the complexity of a wretched catastrophe that kills children on all sides. We are fighting the force of despair that could drown Houston, and me, and you, and Gaza, and Israel, and the entire human family, if we do not rise up and join God’s mission of hope, God’s promise of peace with justice. We are fighting on many fronts.

And in all of this — all of this sadness, all of this anger; all of this anxiety, all of this terror; all of this conflict, all of this death; in all of this, I want you to know, my friends, that you are stitched on my heart, forever, and I love you. As my mentor Kate Sonderegger told you earlier this year, I “join you in your common life before God, and array my strength in your cause.” And finally I am fiercely confident, I am certain, that God the Father rides before us in cloud and brightens our path with fire; that God the Son, the firstborn of the dead – who once was an innocent Jewish Palestinian – God the Son walks reliably beside us; and that God the Holy Spirit fills us with power to meet the manifold challenges of these perilous days.

Come forth, then, good saints, good soldiers, faithful, true, and bold. Come forth and join this mighty battle.