Preached the Seventh Sunday of Easter (Year C), June 1, 2025, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by the Reverend Samuel Torvend.

Acts 16:16-34

Revelation 22:12-14,16-17,20-21

John 17:20-26

Psalm 97

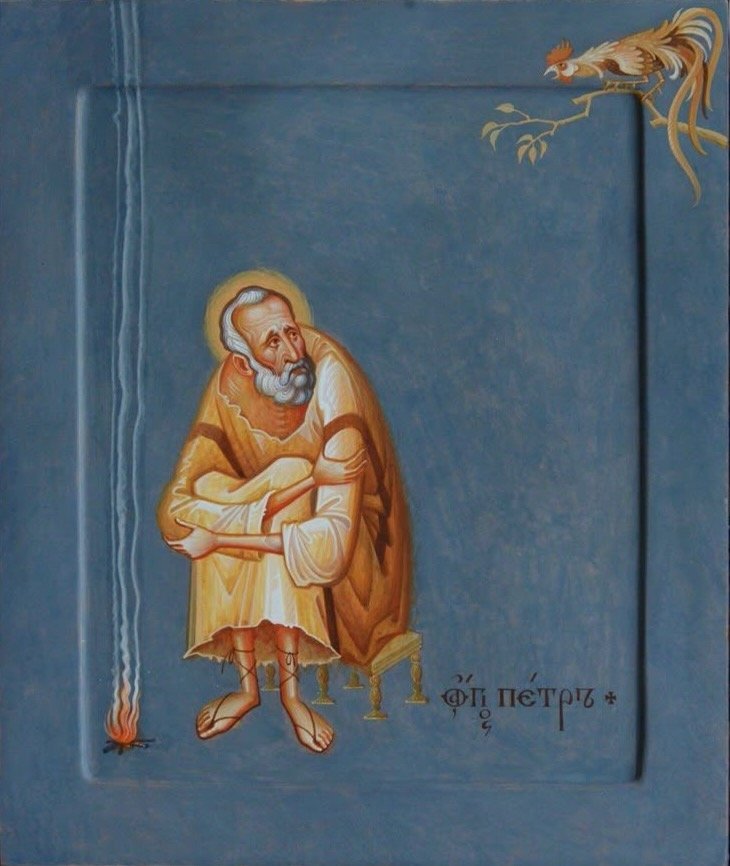

The New Jerusalem, mural by Adam Kossowski

I rarely think about the fact that my parents had to have sexy time in order for me to enter the world. When I mention this in class, my university students begin to look nervous, their faces expressing this question: “Is he going to tell us more than we ever wanted to know about him?” But my point, as I make clear, is this: I did not create myself. That’s a newsflash for some of my students. I am not the mythic “self-made man” or “self-made person.” No: a community of two brought me – and I dare say – brought most of you into existence. And at the moment of my birth we became a community of three: a very natural, biological, relational trinity.

And yet by age 14, I knew that I had three options open to me once I graduated from high school: get a job; join the military; or seek admission to college. It was also clear to me that though my parents loved me, I was to leave home: “Go out into the world by yourself. Off you go.” Does it ring a bell? I was surprised to learn that my cousins in Norway returned to their family compound after school and military service, there to live in close proximity to their parents and grandparents.

How different is the American tendency to exalt the individual: “Leave home and make it on your own in the world.” Perhaps it should not surprise us, then, that the majority of Americans, over 60%, report the debilitating effects of loneliness, what the nation’s former surgeon general referred to as an epidemic of loneliness and isolation. We are so accustomed to entering adult life by ourselves that it seems quite normal. But, then, who acknowledges the terrible price to be paid in emotional, physical, and spiritual health?

I ask my students to reflect on the many persons – most of whom they will never meet – who made it possible for them to be present in class. You know, the laborers who built the dam that creates the hydroelectric power that makes possible the lighting, heating, cooling, and computer use we take for granted. Or the architects, construction workers, electricians, and plumbers who design and build our houses, apartment buildings, and churches. Or the farmers we will never meet who planted, tended, and harvested what becomes our food, our daily bread. I mean if you think about it for any length of time, we are hardly independent agents but rather a people who live in an interdependent world, a world that includes the trees we see around us. Why, one acre of forest absorbs six tons of carbon dioxide and produces four tons of pure oxygen that we and many other creatures breath in.

And so we encounter this tension in our lives: we live in a secular culture that repeatedly sends us the message that “you and you alone matter” and, at the same time, we live in a spiritual culture that prizes the bonds of community and the importance, the absolute importance of relationships. In today’s gospel, Jesus makes this intercession concerning his disciples: “As you, Father, are in me and I am in you, may they also be in us, so that the world may believe that you have sent me.” As these words were being recorded in the Gospel of John, the editor of the fourth gospel was well aware of the fact that Christians were prone to tribalism: to claiming that their one experience or one understanding of the faith, of God, of ethics was the one and only way – the very definition of fundamentalism, be it conservative or liberal. Why, then, would anyone want to participate in a spiritual culture, a spiritual community, that promotes divisions rooted in ethnicity, gender, economic class, or ideology? Thus the intercession of Jesus is an aspirational prayer for you and me: “may they also be in us,” – may they be – a prayer that asks you and me for a good measure of intellectual and spiritual humility; a prayer that pleads for the one thing our world desperately needs and is seemingly incapable of creating and nurturing: a community of relationships marked by self-giving love.

During his presentation before the ordination of our new bishop this past September, Michael Curry, the former presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church said this: “After I was elected to this office, I looked for research on how Americans perceive Christians. What I found was disturbing. While the vast majority of Christians think of themselves as loving or compassionate, more than half of the non-Christians surveyed found Christians, both conservative and liberal, to be judgmental and arrogant. Indeed,” he continued, “when young adults were asked if they saw Christians as loving, the majority were surprised that the word ‘loving’ would be associated with Christians.”

But of course that word “love” can mean many things. When it is used in English translations of the New Testament what we don’t see or hear is the original Greek word agape: love as an action, action serves the wellbeing of someone else, that nourishes relationship with others.

Truth be told, we live in a time in which such love is in short supply as aid to people caught in poverty in other countries is ended; as food is denied to hungry children by the federal government; as medical assistance to those in need is tossed out the window; as protections for wetlands, water, air, and soil are rescinded. What did Jesus say? “May they become one, so that the world may know that you have sent me and have loved them.” Who, then, are we called to be in this chaotic time? Why nothing less than a living cell of health and vitality in the body politic; that yeast which can leaven, enliven the lives of our friends on the street; that love which gives itself away for the good of another, why even a stranger.

And so I wonder: will our eating and drinking of the Body and Blood of the One who poured out his life for others nourish in you and me the pulse of his love and so lead others to give thanks for our commitment to their wellbeing?